Americans Seen: A Theater of the Streets in the Pre-Digital Era by Sage Sohier

Welcome to this edition of [book spotlight]. Today, we uncover the layers of 'Americans Seen,' by Sage Sohier (published by Nazraeli Press). We'd love to read your comments below about these insights and ideas behind the artist's work.

Photographing real people means stepping into their world.

It’s about more than just capturing moments; it’s about understanding people and their stories. In Americans Seen, Sage Sohier focused on trust and collaboration, creating portraits that feel personal and honest. Her approach shows how small, everyday interactions can reveal so much about a person’s life.

In the 1980s, the streets of America were full of life.

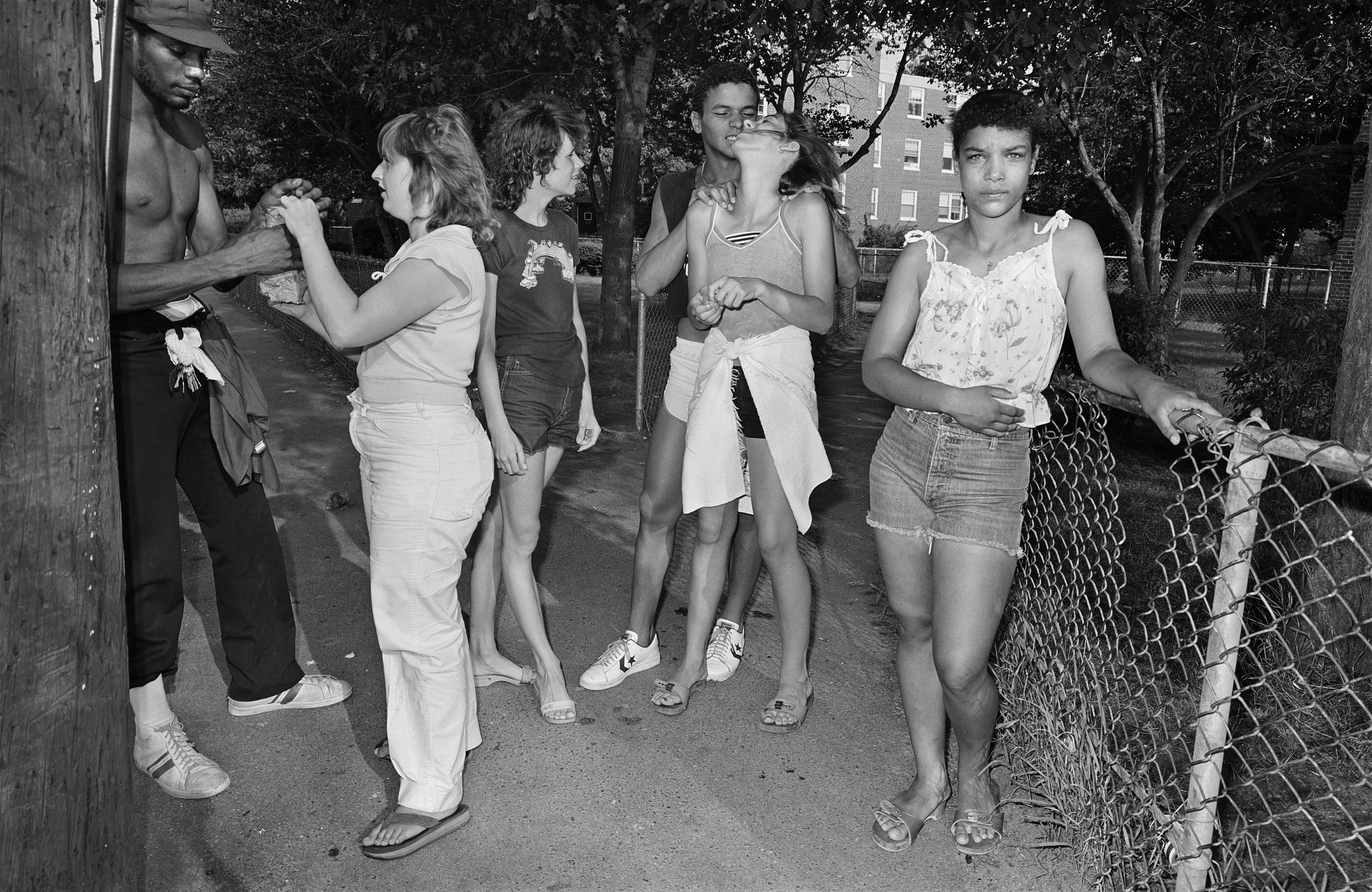

People spent time outside, neighborhoods were active, and families connected without distractions. Sohier’s photographs capture this energy, focusing on working-class and ethnic communities across the country. Her images offer a snapshot of a time when connection felt simpler and more immediate.

The pre-digital streets of America hold secrets worth seeing.

The Book

Americans Seen by Sage Sohier is an evocative exploration of American life in the late 20th century, capturing the spirit and diversity of working-class and ethnic neighborhoods during a transformative period in the country’s history. Spanning the years 1979 to 1986, this collection of black-and-white portraits presents a pre-digital world where families, children, and communities gathered outdoors, creating a “theater of the streets” that was rich with stories and connections.

Drawing inspiration from iconic photographers such as Robert Frank, Helen Levitt, and Diane Arbus, Sohier brought her unique perspective to documenting America. What sets her work apart is her collaborative approach: by seeking permission and engaging with her subjects, Sohier was able to build trust and create images that feel deeply personal and honest, blending art and documentary photography.

Her photographs traverse a wide geographic range, from Boston’s vibrant neighborhoods to rural West Virginia, small-town Pennsylvania, and the expansive landscapes of Utah. Each location contributes its own visual and emotional tone, reflecting the richness and complexity of American life. Using wide-angle lenses and on-camera flash, Sohier’s technical choices further enhance the sharpness and depth of her storytelling.

This remastered edition, published by Nazraeli Press, revisits and preserves Sohier’s timeless work for a new generation. Featuring 51 duotone plates, the book is a tribute to the connections and narratives that define humanity, offering a poignant look at an era of American life shaped by authenticity, spontaneity, and community. (Nazraeli Press ,Amazon)

Concept and vision: What inspired you to create Americans Seen, and how did your experiences as a young photographer in the 1980s shape your approach to this project?

As a young photographer, I was inspired by many different photographers and the American road trip seemed to be a rite of passage for photographers at that time. Robert Frank’s “The Americans,” was an inspiration, as were Helen Levitt’s photographs of children on the streets of New York and August Sander’s “People of the 20th Century.” I loved Diane Arbus’ psychologically acute portraits and Garry Winogrand’s ability to capture amazingly complex candid street scenes.

As I started to photograph, I discovered that when I asked permission before photographing people, I felt more comfortable and got better pictures; that led to a more collaborative and less candid approach.

Exploration of themes: Your photographs capture working-class and ethnic neighborhoods with a candid intimacy. How did you build trust with your subjects, and what themes were you most drawn to explore?

Most of my interactions with the people I photographed outside were quite brief. I think they decided to trust me because I asked permission (and quite often took “no” for an answer) and because I was young and unthreatening. I’m sure that being a woman helped too.

Do you think this collaboration changed the way you approached or understood your subjects, compared to if you’d taken a more candid approach?

If you take a candid picture, you don’t get to know your subjects at all (except from what you can see as you’re photographing). So yes, asking permission, talking to people and collaborating with them does give you a different kind of insight into them. You get more information, although it’s information that’s somewhat colored by introducing yourself into the scene.

Capturing everyday life: You describe your photographs as a “theater of the streets.” How did you approach capturing the unscripted moments of daily life while still conveying a sense of narrative?

I had a strong formal vision of how I wanted the photographs to look and that seemed to help unify the work aesthetically even though my stated project of “People in their Environments” was quite wide open.

How did you decide which moments to capture so they’d feel unscripted yet still convey a sense of narrative? Were there times when you felt like the ‘play’ was unfolding right in front of you?”

I usually ran up to people whenever I was excited by what I saw—when I could see possibilities in the situation. Of course, when you ask permission “to photograph you just the way you are” everything changes at first and you have to wait until people lose some of their self-consciousness and get back to doing some semblance of what they were doing when you first saw them.

Geographic diversity: Your work spans various regions, from Boston to rural West Virginia and Utah. How did these locations influence the visual and emotional tone of your images?

It was stimulating to travel to different regions and environments. Each region had its own character and offered different kinds of environments—triple-deckers in New England; new suburbs out West with trampolines and above-ground pools. I found it more of a challenge to use my wide-angle lens in the flat Midwest and the big-sky West.

Technical and stylistic choices: Your use of black-and-white photography enhances the timeless quality of your images. What technical decisions guided your process, and how did they contribute to the storytelling?

Back in the 70s, most photographers still worked in black and white. I fell in love with wide angle lenses—I liked how they made the foreground large and the background recede and how playing with scale created stories. I also liked to use on-camera flash, so that I could still shoot with apertures of f16 or f11 and render everything sharp even at dusk. Back then I wanted everything to be sharp and visible.

Challenges on the road: Traveling extensively and working in unfamiliar environments must have been challenging. What were the most memorable or difficult moments you encountered during your road trips?

I was fortunate that my husband was able to travel with me some of the time. It made me feel a bit protected, and also provided company in the evenings. Staying in motels alone was never one of my favorite activities—even though I always managed to avoid watching “Psycho.” When you engage with people by asking permission and talking to them, you’re much less apt to run into problems.

Cultural and historical reflection: How do you see Americans Seen contributing to the broader cultural and historical understanding of American life in the late 20th century?

It’s not for me to say…

Considering your recent publication, Passing Time, which revisits unprinted photographs from 1979 to 1985 and captures the relaxed sensuality and spontaneous connections of the pre-digital era , how do you perceive the evolution of intimacy and connection in American life when comparing the subjects in Americans Seen to those in Passing Time?

The pictures in Americans Seen and Passing Time were all part of the same project at the time: Americans in their environments. The main difference is that many of the images in Passing Time were unprinted until recently.

Balancing art and documentation: Your work walks a fine line between art and documentary photography. How do you balance aesthetic considerations with the authenticity of the subject matter?

Yes, it does walk a fine line. It’s documentary in the sense that I’m photographing real people in real situations. But because I ask permission, it becomes more of a collaboration between me and the people in my pictures. It’s still “authentic,” but I have more influence on the photograph because of our interaction.

Advice for emerging photographers: For photographers interested in capturing the essence of everyday life, what lessons from your experiences creating Americans Seen would you share to guide their work?

Approaching people politely and with energy and enthusiasm is key. Having a project or a theme that you can name for people is helpful. Honesty about what you’re doing and where the pictures might end up is important. Agreeing to send people pictures if they want them is also important (it’s a lot easier these days, since you can send jpegs instead of mailing actual prints like I did in the 80s). And you do have to be out there a lot looking for possible pictures. When you’re out there, wonderful and surprising things tend to happen.

To discover more about this intriguing body of work and how you can acquire your own copy, you can find and purchase the book here. (Nazraeli Press ,Amazon)

More photography books?

We'd love to read your comments below, sharing your thoughts and insights on the artist's work. Looking forward to welcoming you back for our next [book spotlight]. See you then!