The Injustice of the Huddled Masses of the Homeless By JM Simpson

Welcome to another captivating photo essay, this time by JM Simpson We'd love to hear your thoughts. Feel free to comment below and, if you're interested, share your photo essay with us. Your perspectives add valuable dimensions to our collective exploration.

Homelessness isn’t just statistics.

We pass by people sleeping under bridges, curled up in doorways, or huddled under tarps, barely noticing them. But each of them has a past, a reason they ended up here, and a future that depends on whether society decides to help or forget. JM Simpson has spent the past two years photographing and talking to homeless men and women in Olympia, Washington. He doesn’t take these photos to make art—he takes them so people can see what they choose not to.

This is not just a local problem.

Over 770,000 people in America are homeless right now, and the numbers keep rising. Some lost jobs, some aged out of foster care, some escaped violent homes—there is no single story, no single cause. But the result is the same: people left behind, struggling to survive in the shadows of cities that move on without them. JM Simpson doesn’t care about arguments over who deserves help. He cares about showing the truth and making people ask themselves: Why do we allow this?

Homelessness isn’t just statistics—it’s faces, names, and stories we ignore.

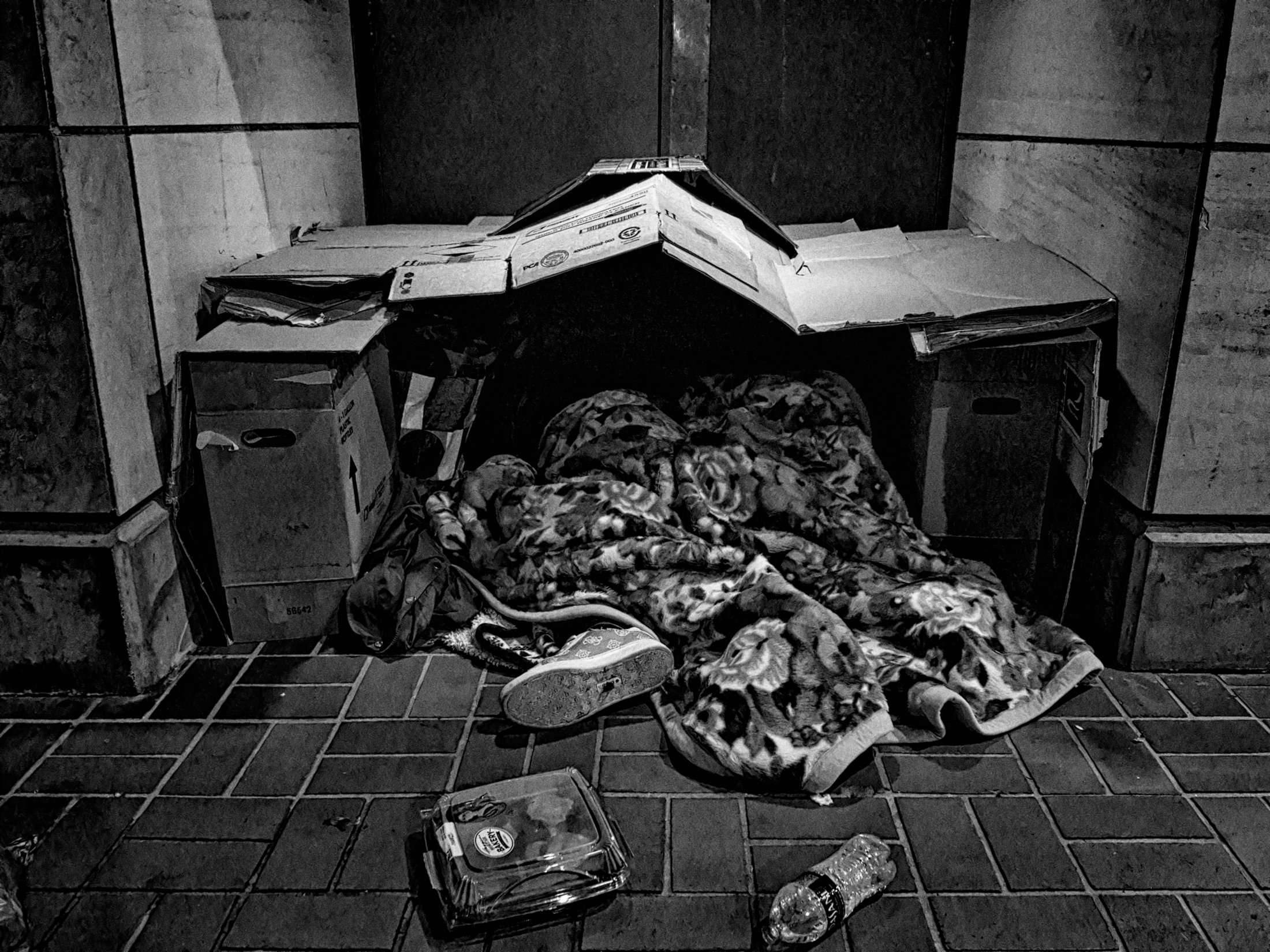

Hard Sleep

The last six lines of Emma Lazarus’s 1883 sonnet, “The New Colossus,” read as follows:

“Keep, ancient lands, your stories pomp! cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

In these measured words – which appear on the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty - Lazarus contrasts the old and the new – the difference between what the old world of the past had offered to humanity with what the new world of America could offer.

But times change, and not always for the best.

As a documentary photographer who has for the past two years worked amongst the homeless men and women in Olympia, Washington, I am reminded of “the huddled masses” and “the homeless” who now in early 2025 number over 770,000 in this country.

I think the point of documentary photography is to momentarily hold life still – to transfix viewers - in order for them to see, understand and then act to correct an injustice.

It is the injustice of people having to live under cardboard, tarps, sleeping in doorways, seeking shelter in dark tunnels, rummaging through trash containers and standing in the rain and snow.

What follows are 15 photographs of homeless men and women yearning to live in a safe and affordable home.

Lady Liberty’s lamplight should also shine on a door for them. - JM Simpson

Covered on the Curb

What initially inspired you to begin documenting the lives of the homeless in Olympia? Was there a particular moment or experience that motivated you to focus on this issue?

What you see in the photograph below is very much what inspired me to begin documenting the homeless in Olympia two years ago this February. Specifically, I saw a homeless man in an alley who appeared to be hypothermic. I called 911 and waited until medical help arrived. As I walked away, I reminded myself that I have over three decades of experiences as a photojournalist and that I could use my experience to help in some way to address the homelessness epidemic in this country.

I have done just that – I am a documentary photographer using the medium of photography to address this growing problem.

Looking to Survive

Your work with the homeless in Olympia is deeply evocative. In your essay, you mention the importance of holding life still to inspire understanding and action. Were there specific moments or encounters while photographing that crystallized this purpose for you?

In “holding life still” I also used the word “transfix,” which means to make a person (in this case, the viewer of the photographs) unable to move or stop looking at something because they are being made aware of a situation that many would rather not look at. I want viewers to literally stand still and reflect on what they see.

It’s not so much that there are specific moments or encounters that have crystallized my thinking about what I want the viewers to see and think about; rather, it is my belief that there is a lot of distraction in present day society – just take a look at your news feed. In order to break through the distraction, I photograph in the manner that I do.

On final thought - in order to tell a story about what one sees when they look at my photographs several characteristics are in play. One, I photograph in black and white because I think color can be distractive; black and white is, well, straight to the point. Two, in the majority of my photographs the homeless person is looking right back at the viewer. I do this deliberately; I want the viewers to see – really see – another human being who is suffering and then ask yourselves, “Why?”

Going back to “Looking to Survive,” why is Joanne standing next to an overflowing dumpster on a cold end-of-January morning? Why do we allow this to happen in our country? Why isn’t housing for all a basic human right?

Hurting

You draw a poignant parallel between Emma Lazarus’s ‘huddled masses’ and the modern-day homeless crisis. Do you feel your photographs can reframe how society views homelessness? What responses or conversations have your images sparked so far?

When I photograph the homeless men and women I meet, I talk with them. Sometimes these conversations last 5 minutes; at other times they can last 25 minutes. I just don’t show up and begin to photograph; I get to know them and once I have a sense they might allow me the opportunity to take a photograph, I ask their permission.

The point is that I get to know many of these individuals and I treat them with the same respect you – or the viewers - want to be treated with. I have noted a number of actions many of the homeless engage in – one of which is being huddled together when it’s rainy and/or cold. That’s when Lazurus’s sonnet crossed my mind for this submission.

I had to smile when you asked what kind of responses my images have sparked. That depends on whom you ask. Some individuals understand that the homeless are human beings who deserve to be helped in confronting the myriad of issues many of them face. This may surprise some people, but each homeless man or women I’ve talked with has a unique – and many times painful - story to tell about their lives. Some folks get this.

Others are simply stupid. I hear about how the homeless deserve what they are because they use drugs or shop-lift or have mental health issues. I also hear that I am enabling the homeless because I am bringing their plight to the attention of city and county public officials.

Frankly, I don’t give a damn what anyone thinks of my work; I think my work speaks for itself – the very definition of documentary photography.

Your essay and photographs highlight the human dignity of individuals facing homelessness. How do you approach building trust with your subjects to capture these intimate and powerful moments authentically?

I touched on this in answering the preceding question; I will broaden my response. Building trust with homeless individuals takes time, understanding, respect for them and a nonjudgmental attitude. And in the majority of meetings, I learned their first names. I realize that my camera can be threatening to a person who has lived a life full of threats and danger. Knowing this, I act accordingly.

If a homeless individual says “no” to my request to take a photograph, I respect that – and I say as much to that person. On the other hand, if a homeless individual says “yes” to my request, I take three or four photographs. I am very aware that in “taking a photograph” I am taking something from them.

Street credibility in photographing the homeless men and women in Olympia is paramount. If that is not there, there will be no trust – and no “intimate and powerful moments” will be photographed.

What do you hope viewers take away from your photographs, and how do you see your work contributing to the broader conversation about homelessness in America?

I have no idea how powerful – or not – one of my photographs can be in moving a viewer to change their views about the homeless or in deciding to act on helping the homeless. I would like to think that those individuals in places of influence do see what I present and then move to act on doing more than what has been done to provide housing for all.

Contributing to the broader conversation in America includes you. I don’t place my work on a website or on Flickr or any other social platform – I don’t give a damn about this kind of exposure.

Rather, I look for high-quality publications and/or news outlets that are interested in my work. This is the reason I contacted you. It is also why my work has been featured on NPR and PBS.

This is a bit long; however, you asked very good and thoughtful questions – they deserve thoughtful answers.

Just like Joanne does.

Cheers,

John