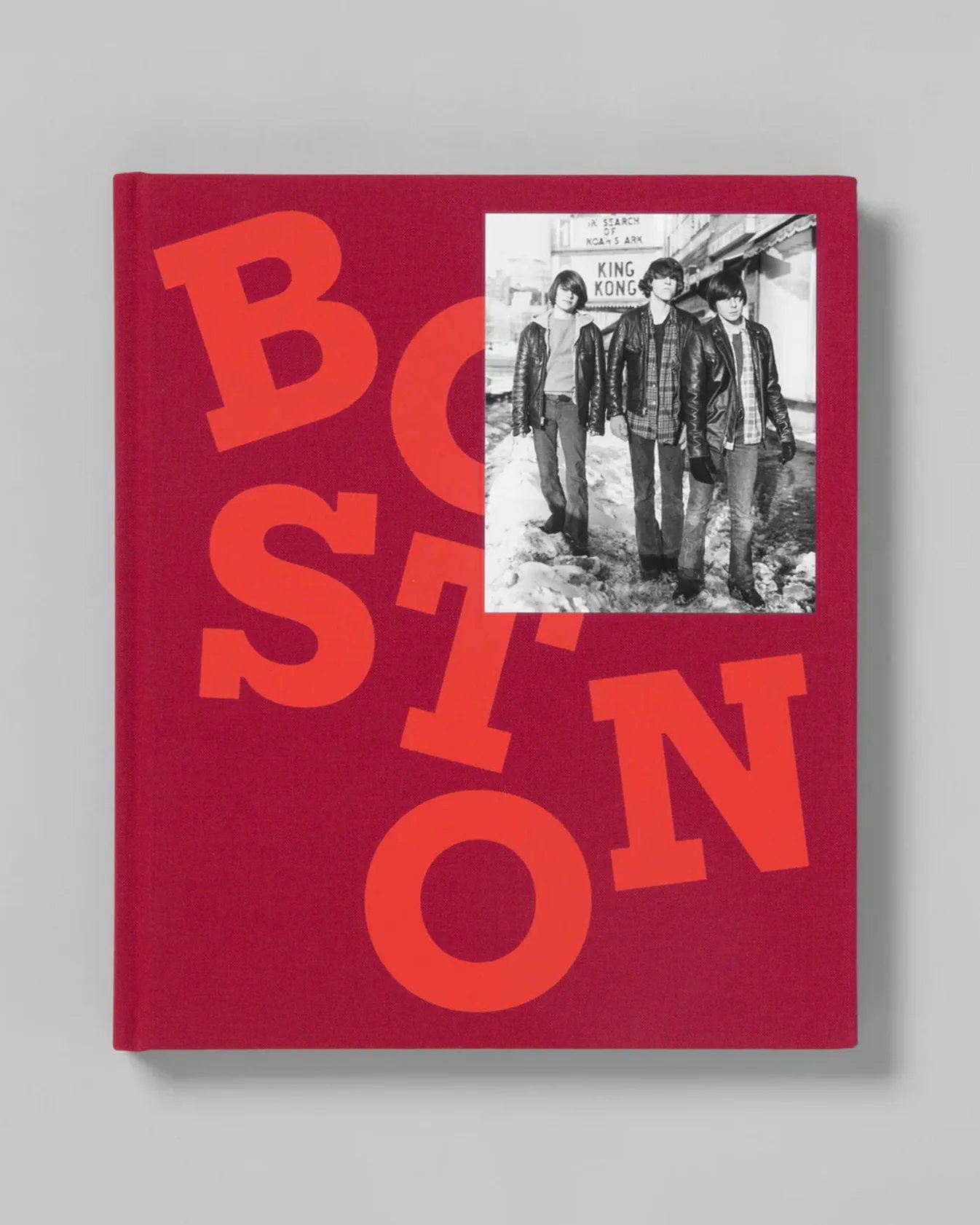

How Mike Smith’s Streets of Boston Captures the Raw, Unfiltered Heart of 1970s Street Photography

Welcome to this edition of [book spotlight]. Today, we uncover the layers of 'Streets of Boston,' by Mike Smith (published by STANLEY/BARKER). We'd love to read your comments below about these insights and ideas behind the artist's work.

In 1970s Boston, Mike Smith wandered with no plan, just a camera.

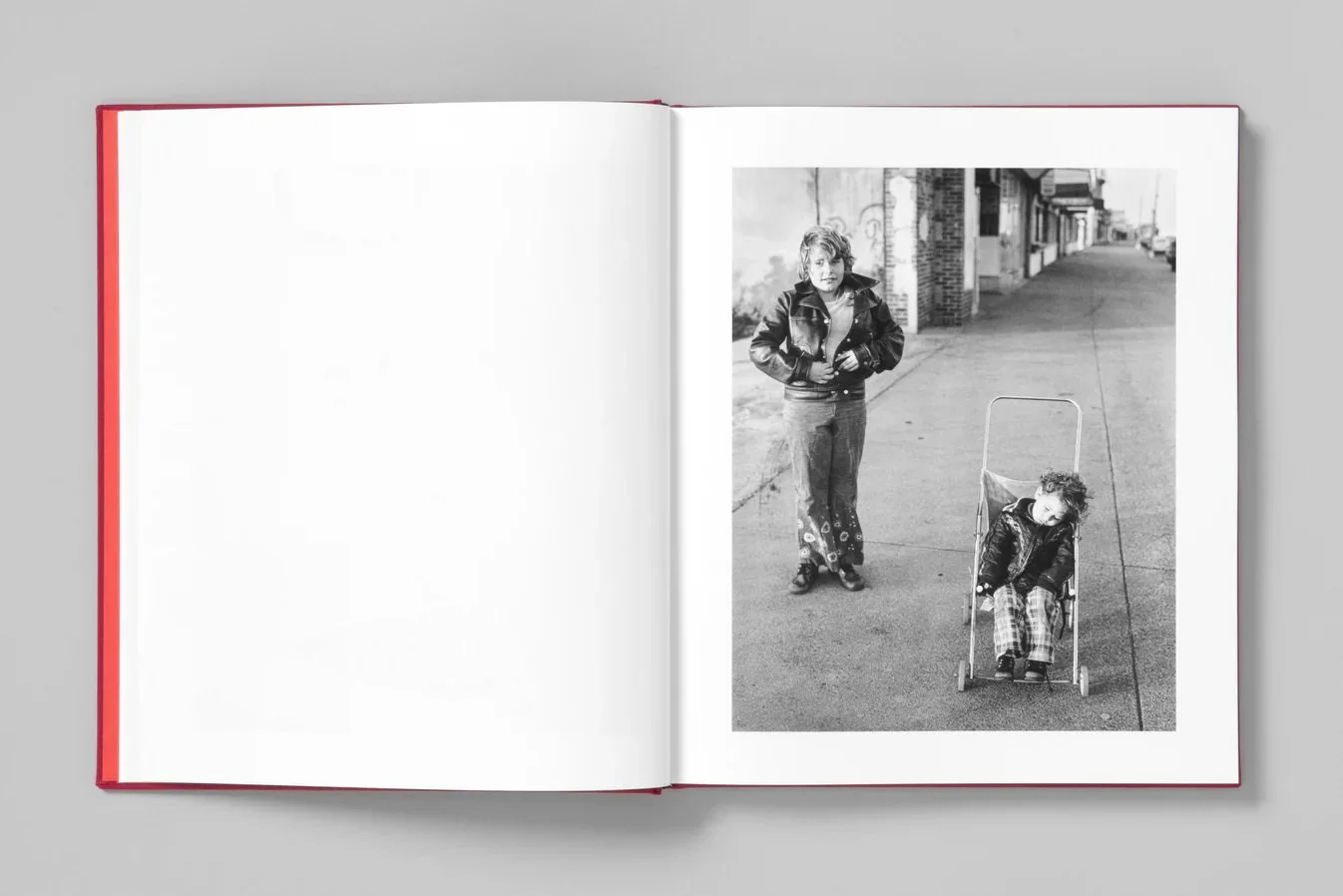

He wasn’t trying to make a political statement or build a career, he was just drawn to people on the street. Smith had studied with photographers like Garry Winogrand and Tod Papageorge, but his own style came from looking without expectation. He carried a heavy Linhof Press 23, asked direct questions, and made portraits that feel honest and unfiltered. This book is about showing up, paying attention, and letting the picture speak.

More than 40 years later, those pictures have become a document of a changing city.

Boston’s streets in the 1970s were full of working-class life, tension, quiet gestures, and chance encounters. Smith never set out to tell a story about society, but the result is full of social detail without trying to explain it. He didn’t chase style or wait for the decisive moment. He trusted his eye and responded to what was in front of him.

Mike Smith didn’t try to document Boston; he just looked.

About the Book

Published by Stanley/Barker, Streets of Boston brings together a selection of Mike Smith’s early black-and-white photographs made in Boston during the 1970s. The book offers a striking visual record of a city rarely seen in such personal and unfiltered terms. With careful sequencing and understated design, the publication focuses attention on the quiet strength of the portraits and the atmosphere of the time. Decades after they were made, these photographs still feel immediate, reminding us of the power of looking closely and with intention. (STANLEY/BARKER, Amazon)

Genesis of the project: What initially drew you to photograph the streets of Boston in the 1970s, and how did your experiences as a Vietnam veteran influence your perspective as a street photographer?

In Vietnam, I bought my first 35mm camera. I photographed my daily activities (heavy equipment operator), my buddies, the landscape, and occasionally Vietnamese people who would either work alongside us or in our camp. Other than that, I did not consider photography seriously at that time. I will say this though: I was accepted at MassArt as a photo major ONLY because I was a Vietnam vet, and they, as a state institution, had a special admission policy for them.

The draw of the street was mostly a response to my studies; workshops with Winogrand, Friedlander, Nixon, as well as studying the works of Evans, Sander, Arbus, Levitt, etc. It was my last semester there I met Tod Papageorge, who later accepted me at Yale. Those artists influenced my perspective directly. Vietnam, other than being the place where my interest was sparked (by a friend’s very cool camera), had little or nothing to do with my foundation in photography as a form or artist expression.

Transition in photographic approach: After an incident in 1976, you switched from a 35mm Leica to a Linhof Press 23 camera, moving from spontaneous street photography to more intimate portraits. How did this change in equipment and approach affect your interaction with subjects and the resulting images?

The Press 23 is somewhat of a beast; big and heavy. There is no spontaneity with that machine. (I recently bought another on eBay and was amazed that I used it so effectively in Boston. The purchase was a pure act of nostalgia, and I quickly sold it, without even putting a roll through it!)

While involved in the work at the Prudential Centre, where the incident you mention occurred, I began making street portraits using the Linhof. I should also mention, at that time in my recent history, I had studied social work at a community college. The idea of working one-to-one was not far from my experience. Having someone injured as a result of my approach forced me to change. The new format/camera largely drove the approach. It had a relatively long lens (compared to the 35mm camera with a wide lens), a shallow depth of focus, and a razor-sharp lens. At 3 feet, it resolved detail beautifully. I wanted to somehow acknowledge the individuality of each person. Articulating the nuanced aspects of one’s physicality is one way to distinguish them visually. What do they say?… God is in the details. (…or was that Tod?)

Capturing the essence of Boston’s inhabitants: Your work is noted for its inclusive, non-judgmental, yet direct portrayal of Boston’s residents. How did you build rapport with such a diverse range of individuals, and what strategies did you employ to authentically capture their personalities?

As I said above, I was in a social work programme prior to attending art school. I suppose some people are less threatening than others, and I may be one of those boring souls whose presence can easily be ignored. It’s flattering to think the work is essential! And I would question the notion of ”capturing their personalities”. (As Winogrand rightfully said, and I believe, the camera sees light on surfaces!)

Each encounter was brief, spontaneous, and direct. I set out each day without expectation, plan, or strategy, much like my work continues to this day. I was interested in photographing people. I recall, at the time, wondering why anybody would bother photographing a tree!

I suppose the “rapport” was, in part, the product of interest in the person’s appearances, which I almost always would comment on. If I met someone with one leg, I would ask right off, “how did you lose your leg?”

Influence of cinematic elements: The cover photograph features three young men standing near a theatre showcasing films like King Kong (1976). How did the cultural and cinematic landscape of the time influence your compositions and subject matter?

I didn’t think much about or know much about film at the time or now. I may have seen a couple of Italian postwar films in school that affected my thinking (De Sica, Fellini, etc.), but I am not, to this day, very smart about film or affected by them. I remember being jealous of the smooth, soft tonality of DeSica’s work and amazed by the range of human experience in Fellini’s work.

Technical and aesthetic choices: Working with a large-format camera requires a deliberate process. How did this technical choice impact the aesthetics of your photographs, and what challenges did you encounter in the dynamic environment of Boston’s streets?

The distinction between large and medium format is significant in terms of detail but, more importantly to me, relative to the shape of the negative. The Press 23 is a camera with interchangeable film backs that provided 6x6, 6x7, 6x9 options. I had a 6x7cm back. That is equivalent to the 4x5 or 8x10 format’s shape. Migrating from 35mm format (2x3 or 6x9 proportions) to 6x7cm (8x10 proportion) means more on top or bottom (or both). In a vertical orientation, that means more room on the sides, which was helpful for the portraits.

The Press 23 was always handheld. The finder is at least 3 inches off-centre from the lens, which was indeed the most difficult part of composing with that machine. Reconciling that characteristic meant I would have to lift and move it to one side for each frame to compensate for the parallax.

I worked as a messenger (on foot) for a while in Boston. My boss allowed me to carry my camera. It was a great choice of jobs because I was dispatched to all corners of the city and entered buildings and offices I otherwise had no business being in. I lived in the Black community, on the edge of Roxbury. That contributed to the environments in which I worked and the range of subjects I encountered.

Evolution of your photographic journey: Reflecting on your early work in Boston and your later projects in Eastern Tennessee, how has your approach to photography evolved over the decades, and what core principles have remained consistent?

As mentioned previously, and still applicable: no expectations, no plans, no script. I wander. I look. Now in a car, rather than on foot. I sometimes ask permission (if I need to get on someone’s property). I am mostly working with landscapes (trees!) using digital cameras as well as the 8x10 film camera. At the centre of it all is a desire to respond to the world around me, which I personally feel is more interesting than anything I am capable of imagining. Presently, I am battling East Tennessee’s lavish green!

Portraying the socio-economic landscape: Your images predominantly feature working-class individuals during a period of significant social and economic change in Boston. How did you approach documenting this context, and what narratives were you aiming to convey through your portraits?

I was not interested, or knowledgeable, about the economy (did I have enough cash to buy paper or film?). To whatever extent my work may have touched on such broad issues I was unaware of at the time, although looking at the work now I can acknowledge some awareness, be it intentional or not. I think as a young artist I was motivated more by learning how to make a photograph and, as it turns out, expressing my innate interest in others. I did not set out to document anything. No plan. No narrative. My choice of whom to photograph was a simple, natural affinity, or attraction to some aspect of the individual’s appearance.

Revisiting and publishing the archive: Decades after capturing these images, what motivated you to publish Streets of Boston now? How has your perception of this body of work changed over time?

Mark Steinmetz suggested I make a book of the Boston work. He and I have known each other since the eighties and I trust his judgement. I can vividly recall dreaming of “having a book” when I was making the work. It was perhaps a motivation, in part, because my teachers all had published their work and I learned so much from books. My copy of Sander’s “Men Without Masks” is frayed. Evan’s “American Photographs” is a tattered workhorse; stained, rode hard and put up wet! Looking at them now is really visiting old friends and a continuance of my learning.

Advice for emerging street photographers: Based on your extensive experience, what guidance would you offer to photographers seeking to document urban life authentically, especially regarding building trust with subjects and navigating the complexities of street photography?

Authentically means having authorship. Personally, I don’t believe we can escape ourselves. Teaching for 36 years showed me the folly of “inventing“ one’s style. A shallow look is not enough. It’s not Hollywood! If you work at it hard enough and long enough, get through all the obstacles (like worrying about style), whomever it is that you are will come out in the work. As far as building trust with others, I think it has to do with being genuine towards them. Sort of like a dog, instinctively they know if you’re a good egg.

To discover more about this intriguing body of work and how you can acquire your own copy, you can find and purchase the book here. (STANLEY/BARKER, Amazon)

More photography books?

We'd love to read your comments below, sharing your thoughts and insights on the artist's work. Looking forward to welcoming you back for our next [book spotlight]. See you then!