The Story of Musicians On The Ganges by Russell Hart

(This is the story behind the photograph—a glimpse into the moment, the process, and the vision that brought it to life.)

How do you capture music in a photograph?

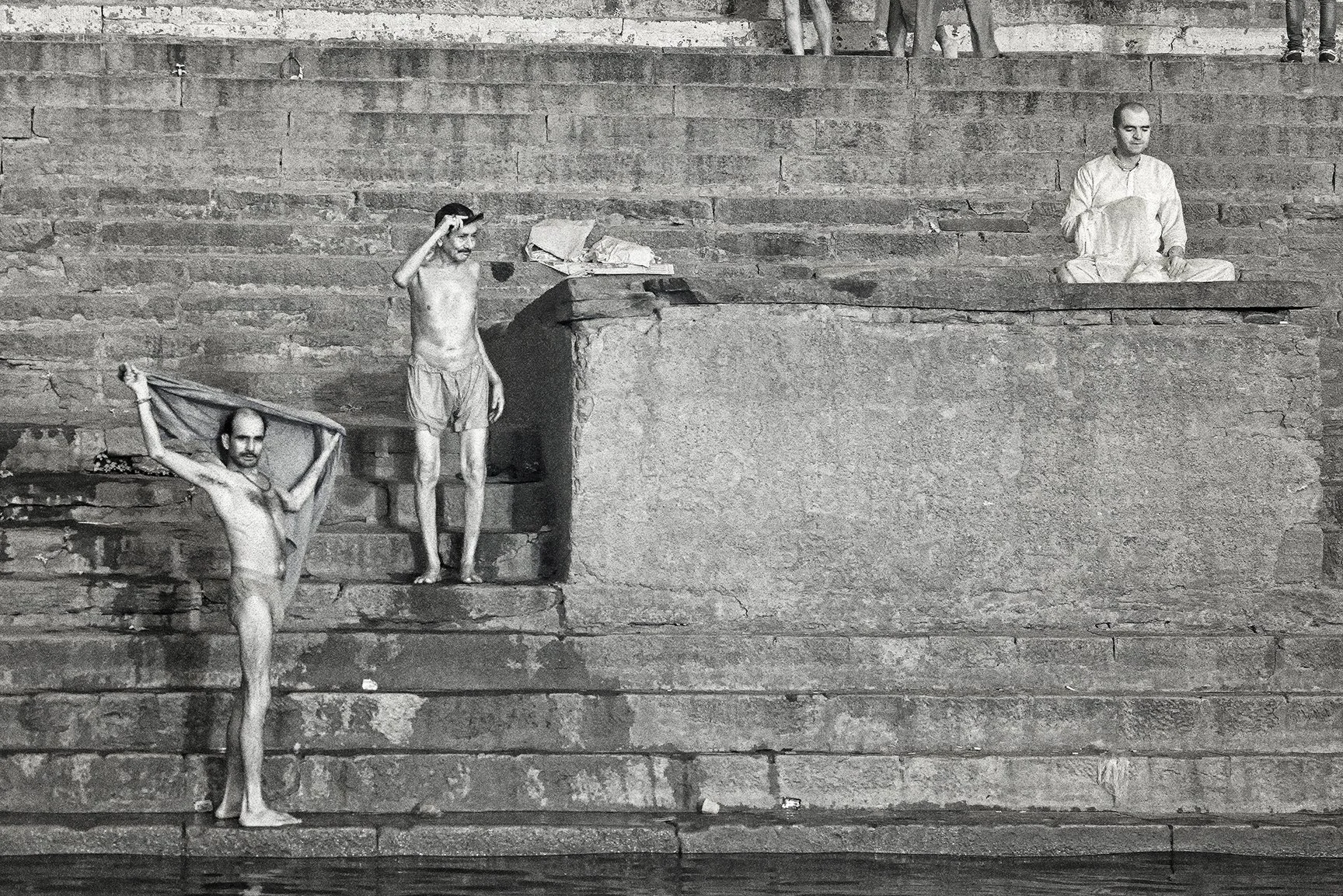

Varanasi is no ordinary city. It’s the holiest place in India for Hindus, where people come to wash away sins in the river and seek salvation after death. It’s also overwhelming for anyone visiting—loud, crowded, and alive with activity at every corner. Photographer Russell Hart had to learn how to photograph this chaos without losing its essence, and what he created is a story of connection, creativity, and discovery.

Just before dawn, a small boat drifted across the Ganges River. The water was dark and smooth, reflecting the faint glow of lanterns along the shore. In the distance, the stone steps of the ghats—massive staircases leading down to the river—were already coming to life. People bathed in the holy water, washing away their sins. Priests performed morning rituals. Smoke from funeral pyres curled into the sky.

In the boat, two musicians sat cross-legged, their instruments resting in their laps. One played the sitar, plucking its strings with quick, delicate movements. The other tapped a pair of tabla drums, creating rhythms that seemed to blend with the sound of the river itself. The music was hypnotic, a mix of tradition and improvisation.

Hart raised his camera. He had spent days exploring Varanasi, trying to make sense of its overwhelming sights and sounds. He had been to India before, but this city was something else—a place where life and death existed side by side, where every street was packed with movement, color, and history.

“India was transformative for me as a photographer,” Hart says. “The great photojournalist Eddie Adams once said that you could drop him anywhere in India, spin him around, and he’d come away with a great photograph. I understand what he meant, but it wasn’t quite that simple for me. I came to India as a photographic minimalist. I quickly realized, though, that there was no way I could impose this aesthetic on such a dense, visually rich place. I had to figure out how to deal, photographically speaking, with the complexity of the Indian world, whether street scenes or landscape.”

“I went to India with my late, great South Indian friend John Isaac, who for decades was chief photographer for the United Nations. John and I ended our trip at Varanasi, a place of pilgrimage for Hindus, for whom it’s the holiest city in all of India. Varanasi sits on the bank of the also-holy Ganges River. Orthodox Hindus believe that bathing in the Ganges washes away one’s sins. It’s said that if someone dies in Varanasi, or is cremated there and the ashes scattered into the Ganges, they will be freed from Hinduism’s cycle of birth and death and achieve salvation. The city is full not only of Hindu temples and shrines but also of holy sites for Buddhists, Jains, Sikhs, and Muslims.”

While walking through the city, Hart and his friend had stepped into a small music shop. The walls were lined with traditional Indian instruments, their polished wood glowing in the dim light. He and John had always loved Indian music, and as they browsed, they got to talking with two local musicians—a sitar player and a tabla player.

“We were planning to have a boat take us out on the Ganges early next morning, and it occurred to us that we could hire these musicians to provide musical accompaniment for our adventure. We asked them to come along, and they seemed more than happy to agree.“

“All along along the bank of the Ganges in Varanasi are ghats, massively high and wide stone steps that lead down to the river. The ghats are a hive of activity where visitors encounter everything from open funeral pyres to artists angling to paint your face in the style of the nearly-naked Sadhus (Hindu ascetics) working the waterfront for alms. We met our musicians before dawn at one of the ghats, and set out in a small boat. With long oars the boatman rowed us out across the smooth water of the Ganges.“

The boatman, an older man with a strong grip on the oars, rowed them out into the quiet river. The sky was still dark, but slowly, the first light of day crept over the horizon. On shore, the city was waking up—people performing morning prayers, monks meditating, merchants setting up for the day. Fires from overnight cremations still burned, their flickering glow reflecting on the water.

“For me, the moment was transcendent,” Hart says. “Despite the bloated corpses of cows that floated past us. My initial worry about the water being splashed around by the oars— immune Indians bathe without issue at the bottom of the ghats, but Westerners can become very ill if they ingest the water— faded with every stroke.“

At first, Hart focused on photographing the ghats. Using a long lens, he zoomed in on small moments—the expressions of people praying, the texture of the ancient stone steps, the golden light of sunrise hitting the water. But then, he turned his attention back to the boat.

The musicians were completely lost in their performance, their fingers moving fast across the strings and drumheads. Hart wanted to capture their energy without blurring the motion.

“I put a 35mm moderately-wide-angle lens on my camera, and turned it toward the musicians. Their arms and hands were moving very fast as they played, so I set a higher shutter speed than I’d been using for the ghats in order to freeze their motion. Even so, and rather than simply shooting in bursts, I tried to time my exposures to coincide with moments when the musicians had briefly paused, making just one shot at a time. The picture here, taken at the end of a long raga, was the best of numerous frames. It’s not typical of my photographic work in that it portrays two clearly identifiable, frame-filling figures engaging in their own creative endeavor— that being music, something photography can’t capture. But it was too good a subject to pass up in the name of a foolish consistency, to use Ralph Waldo Emerson’s memorable phrase.“

One shot stood out among the rest—two musicians, fully absorbed in their music, framed against the rippling water of the Ganges.

India had changed the way Hart approached photography. He had arrived thinking he could simplify the chaos, but he left realizing that some places aren’t meant to be tamed—they’re meant to be experienced in their full complexity.

“My time in India was unforgettable. It was one of those rare experiences when a place is so powerful in its sensory properties that photography is simply subsumed by it. I remember riding at dusk in an open jeep through the small Rajasthani city of Sawai Madhopur and having my senses simply overwhelmed. The streets were full of end-of-day activity. Small groups of feral pigs ran along the road; cows, being sacred, enjoyed naps in the middle of it, forcing traffic to dodge them. The air was full of smoke from evening cooking fires. Bells and calls to prayer rang out. I could feel and taste the dust in the air. I have to say that India is one of the hardest places to be that I’ve ever experienced, but I would not have missed it for the world.”

More stories: